Informal Work in the Public Space: Adaptation and social resilience in Colombia

e-mail: juancho@benitez.co

Photo by Thiago André @thiagoandreh

Although a vital element of urban life, informal workers in public spaces are often stigmatized and neglected by traditional policies and academy. Despite their vulnerability, they can develop valuable resilience skills and influence spatial dynamics. In order to leverage their innovation potential, our cities should provide a more flexible regulatory framework, transforming the public space in a safe platform that fosters inclusion and healthy competition.

Paola Daza, a street vendor in Bogotá, tells a story that is unfortunately all too common in Colombia. In the beginning of the 2000s, her father was murdered on the family’s coffee farm in Eastern Antioquia during Colombia’s internal war, which has plagued the country since the mid 1960s. As a result, she was forcedly displaced to the capital city, Bogotá, along with her mother and four siblings. In 2003, at the age of 15, and without a high school degree, she became pregnant. Having to look after the newborn, she was forced to become a street vendor. Hoping to support her new family, she finished high school during the weekends, and given her outstanding performance, she was offered a scholarship to pursue a technical career in management. She found a job, from which she resigned after eight months due to the low salary and the extensive and inflexible working hours. She had to come back to her ‘chaza’ (a colloquial name for a street vending stall) but her dreams did not stop there; a few years later, she entered university. She received her psychology diploma, entirely financed by her informal business, in June 2018.

Figure 1. Paola and her husband in front of their ‘chaza’.

Paola’s story is endemic to many parts of Colombia as well as much of the world. Around 200,000 people work informally in the public space in Bogotá alone. That does not even compare with the total amount of non-agricultural informal workers which, in the case of Colombia, accounts for 48% of the working population and in some parts of the world - like in South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa - for more than 70%.

Even though informal workers are an integral part of daily life for millions of people around the world, they are often criminalized, diminished or abandoned, and suffer from constant stigma and exposure to all kinds of vulnerabilities. Usually, the same governmental institutions who neglect their basic needs and rights, punish their practice, which further aggravates their socio-economic vulnerability.

Despite these adverse conditions, informal workers find ways to survive within threatening environments. Many of them have found in the public space the perfect platform to carry out their work and earn a living. Out of the necessity to constantly adapt to the hassles of working ‘on the streets’, Informal Workers in the Public Space (IWPS) have revealed attributes that could be associated with the nature of social resilience.

However, their work, which influences social and spatial dynamics, is still largely invisible and not yet well-understood. The lack of evidence and the traditional linkage of this practice with illegality and underdevelopment have hindered authorities, academics and policy-makers from providing adequate and more effective solutions for this widespread phenomenon.

To help fill this gap, I conducted research in Bogotá that sought to find empiric evidence of the adaptation and survival mechanisms of the IWPS and draw connections to the creation of social resilience. This way, lessons could be drawn on how IWPS practices could be embedded within the urban resilience agendas and extended to other vulnerable communities or groups.

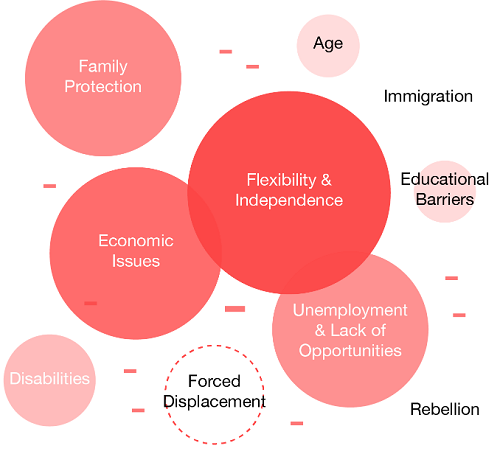

Entering the informal economy is an adaptation mechanism to cope with personal or professional life experiences (See Figure 1). But this is just the beginning of a series of adverse conditions or threats to overcome (see Figure 2). The IWPS constantly respond to those threats, recover and devise mitigation mechanisms for the future.

Figure 2. Main ‘triggers’ leading to entry in the informal economy according to semi-structured interviews. (Source: Author)

Figure 3. Risks associated with the informal work in the public space according to semi-structured interviews. (Source: Author)

The Downside

The most striking result of my study came from very low levels of confidence in the political and institutional sphere. Corruption, bribes and political volatility are just some examples of the reasons why the IWPS have lost full confidence in institutions like the police, Congress, and local representative bodies. This hatred and mistrust is producing a snowball effect in their minds, as the pressure and abuses just continue to increase. In addition, official data from the Institute for the Social Economy (IPES) confirmed very low access to health protection and education. Most of the workers are protected by Colombia’s subsidized social security scheme, which is characterized by poor coverage and degrading treatment. Finally, almost 70% of the IWPS haven’t finished secondary education, with the elderly being the least educated.

The Positive

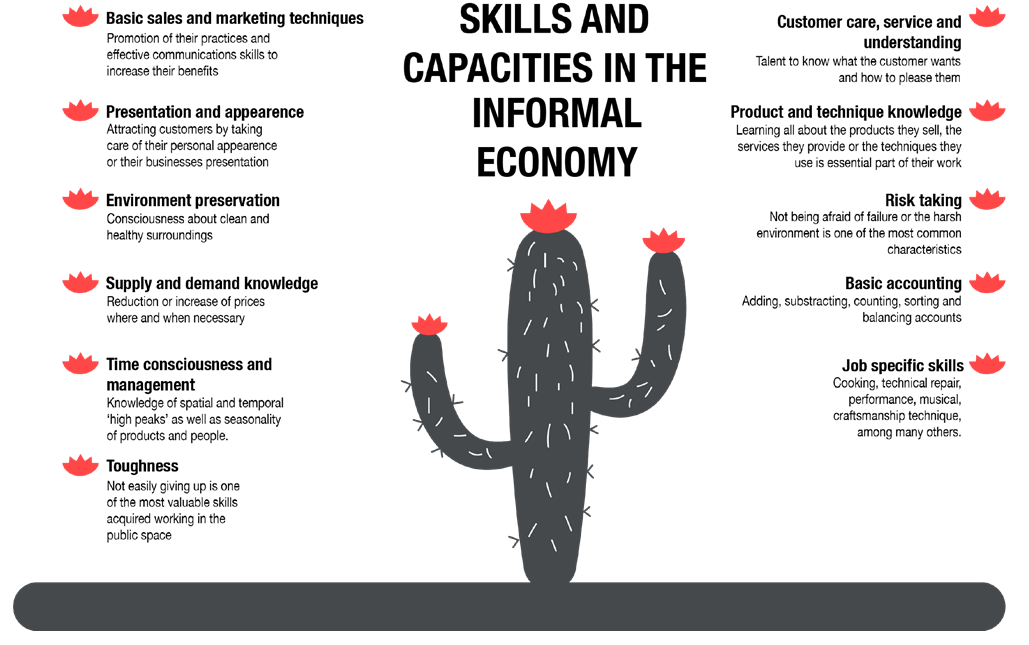

Not having a formal education does not imply that informal workers do not have valuable skills, contrary to what traditionalist approaches portray. By experience, observation or trial and error, the IWPS have acquired most of the capacities necessary to carry out their work (See Figure 4). The latter is complemented by their incredible networking capacities, evidenced by the creation of meaningful social links with other workers, citizens, authorities or institutions. Far from being mere social relationships, these links have proven to be effective when the integrity of the IWPS is threatened.

Figure 4. Skills and capacities in the Informal Economy. (Source: Author)

Let's Talk About the Space

In terms of their working space, it is visible how the more compact, enclosed and ‘protective’ the space, the more bonding among informal workers takes place. But the public space is not just a contested arena where some individuals create livelihoods. It is an open platform for people to showcase their abilities and inventions. While the presence of informality in the public space could create chaos, it can also become an attraction, enriching cultural, social and spatial environments. Many IWPS have made the best possible out of their limited resources out of creativity, resourcefulness and ingenuity. The desire to offer the best product, performance or service drives some individuals to stand out from the rest (See Figure 5).

Figure 5. Creativity, resourcefulness and differentiation as engine of innovation. (Source: Author, unless specified)

Further Questions

The evidence found reinforced the idea that the IWPS' long story of adaptation has carried alongside a creation of social resilience, which has been largely overlooked. However, more and more evidence is needed to support this assertion. Its importance relies on how this can trigger debates that question the applicability of traditionalist approaches towards the Informal Economy, which have proven ineffective, and to offer an alternative vision of the public space as a platform with the potential to foster inclusion. Adopting authoritarian and punishment-based policies towards the IWPS goes against the potential for innovation and social resilience per se. We still owe them, and our cities at large, a legal framework flexible enough to accept the public space as safer platform to promote a healthier culture of competition, creativity and innovation.

For full access to this research please follow the link below: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Juan_Benitez_Bustamante

Juan Sebastián Bustamante holds a MSc in Integrated Urbanism and Sustainable Design from the University of Stuttgart, Germany. He is also a Civil Engineer from Los Andes University, Colombia. Through his academic and professional career, he has channeled his efforts and capabilities towards more just and livable cities.